![]() The Journal of

Public Space

The Journal of

Public Space

ISSN 2206-9658

2022 | Vol. 7 n. 2

https://www.journalpublicspace.org

Understanding Inclusive Placemaking through the Case of Klostergata56 in Norway

Ursula Sokolaj

NTNU & StudyTrondheim, Norway

ursulaso@stud.ntnu.no

Abstract

Public participation and the placemaking approach are receiving continuously increasing attention and are therefore likely to become, in a near future, the norm of shaping our cities. They are instruments of local democracy, enabling citizens to stake a claim and exercise their influence on the city, repositioning them from recipients to active participants in this shaping. Research has shown that these democratic processes are the best way to ensure better physical environments, while also bringing social development. However, this attempt to shift from government to governance by power redistribution can at times pose a challenge to democracy, by repeating existing power relations between participating actors. If representation is not done right and communities are not equally engaged, the social benefits are at stake and issues of inclusion and exclusion arise. The need for assessment in this field is therefore highly relevant, but little progress has been done in developing measurable evaluation tools.

This article is based on action research, following as a case study the process of co-designing Klostergata56, a small, underutilized public space in the Norwegian city of Trondheim. It presents a new framework of evaluating a participatory process, applied to the project to investigate its level of inclusion.

Results of the study showed that the process had significant limitations to being inclusive to the expense of marginalized groups, due to unequal participation of stakeholders and differences in levels of nurtured social capital and civic trust. The challenges highlighted by the research make it possible to identify lessons for further processes to be more inclusive. Until such challenges are addressed, participatory placemaking will continue to be a trial-and-error process, therefore bound to repeat, at least to some extent, the inequality patterns present in a society.

Keywords: public participation, placemaking, inclusion, public space

To cite this article:

Sokolaj, U. (2022) “Understanding Inclusive Placemaking Processes through the Case of Klostergata56 in Norway”, The Journal of Public Space, 7(2), 193-204. DOI 10.32891/jps.v7i2.1495

This article has been double blind peer reviewed and accepted for publication in The Journal of Public Space.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial 4.0

International License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

![]()

Introduction

Public spaces are the physical and social glue that define and enrich city life, by giving people the opportunity to relax, exercise, discover, exchange, socialize and express themselves (UN, 2015). Their design and management is responsible to understand and serve the public good, so that they respond to the needs of their users, relate to their physical and social context, and enhance individual well-being (Carr, et al., 1992). Their value and impact are closely tied to everyone’s right of access, and freedom of claiming temporary ownership – limited only by the rights of others (ibid).

Citizen participation intends to tap into the tacit knowledge of the intended users of a space, to best comprehend the social context and the different perspectives on its use and meaning, while also granting citizens the right to shape their own environments (Carr, et al., 1992; Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernization, 2019).

Although in theory citizen engagement is closely tied to deliberative democracy, in practice the correlation is not always positive. Claims over a public space can be made by different organizations, individuals, or social groups, with varying needs and wants regarding the outcome. Involving all actors equally and intersecting differing interests over the same space can be a challenging process, which tends to favour powerful groups and leave behind those who do not control resources or are more passive in voicing their opinion (Madanipour, 2010). This brings about issues of inclusion and exclusion, which go hand in hand with social inequality (Iwinska, 2017). Negotiations should therefore be reached through inclusive processes, where everyone’s voice, but especially the excluded urban groups’, is involved (UN, 2015). Inclusion is an integral theme of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted in 2015 by all member states of the United Nations including Norway. The commitment towards leaving no one behind is especially underlined by SDG 11 on sustainable cities, which emphasizes the inclusion of women, children, people with disabilities, older persons and ethnic minorities, along other historically marginalized groups.

The case

The site of the Klostergata56 project (Figure 1) is located in the Norwegian city of Trondheim, which is home to country’s largest university, NTNU. The project connects into the wider development plans aiming to turn Trondheim into a vibrant sustainable city, that integrates the campus with the urban environments and enables locals and students to live in cohesion.

A strong focus in these plans is given to the creation of high-quality urban spaces, with the site in question identified as one that needs improvement. A SIT (Student Association in Gjøvik, Ålesund and Trondheim) owned student accommodation lying on the edge of this site is currently deteriorating. To acquire permit approval for its reconstruction, the developer is expected to also upgrade the adjacent public space.

Although small, due to its direct link to the riverside trail and the immediate location of the neighbourhood’s supermarket, the site is regularly frequented by most stakeholders in the area. However, today it mainly serves as a passageway and an underutilized parking lot, and it does not attract users to stay for a long period of time. SIT’s proposal for the redesign of the space pursues therefore a primary goal of increasing outdoor activity at the location throughout the year. The impetus for a participatory process were the competing interests over this vision with the neighbouring rehabilitation

centre (BUP), whose three facilities define a larger share of the site’s perimeter. The task to carry out a co-design process engaging the priorities of both these central stakeholders, but also the perspectives of the broader neighbourhood and general passers-by, was taken over by StudyTrondheim, a grassroots coalition between the students, the municipality, the university, and other local partners.

Figure 1. Klostergata56 site location.

Participation in planning is one of the key points in the Planning and Building Act in Norway. However, the majority of the local zoning plans today are executed by private actors who treat participation as a box that needs to be ticked for processes to be finalized (Falleth et al., 2010). In other words, the community is only involved within the minimal legal requirements - giving feedback at the late stages of the process, once the main content of the plan has already been set (Fiskaa, 2005; Falleth and Hansen, 2011).

Klostergata56 is a pilot project in this direction, since StudyTrondheim is committed to pursuing a highly deliberative process employing the principles of placemaking, involving the citizens through all stages - from the definition of project goals to the design outcomes. Promoting the approach to further developments in Trondheim would contribute to creating a city shaped from its own citizens by encouraging a local culture and practice for participation.

The framework

Despite citizen participation becoming an increasingly followed

practice in planning and design in the international sphere, few projects seem

to thoroughly assess their process. The reason for this could be linked to the

pressure to label them as successful (Silberberg et al., 2013), coupled with

the limited progress in developing measurable

assessment tools. But it is only through comprehensive and detailed evaluations that the successes, failures, and emerging lessons can be identified. This would advance the body of knowledge in the field, allowing future participatory processes to truly realize their democratizing potential instead of repeating the same mistakes (EIPP, 2009).

The opportunity to perform as one of the facilitators of the Klostergata56 project allowed the author, for the purpose of a Master Thesis, to closely observe and reflect on the challenges of citizen participation, often overlooked by the idealized portrayal of the process in literature. These observations were supplemented by interviews with project participants and local planning experts.

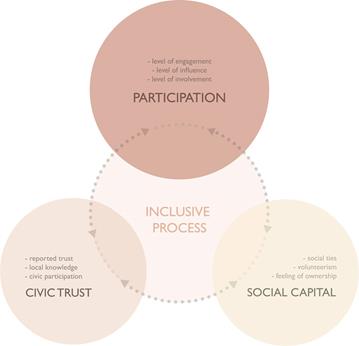

Figure 2. Evaluation framework (adapted from Sokolaj, 2021).

In order to analyse how inclusive the process was, the research firstly compiled existing resources, to propose an evaluation framework with concrete metrics and indicators. This new framework (Figure 2) ties together civic trust, participation, and social capital of an area as drivers of inclusion in a placemaking process. Civic trust reveals community’s perception of meaningful involvement, in terms of institutional trust, rate of civic engagement, and local knowledge of participatory processes. Social capital, on the other hand, is measured by the existing social ties in the area, volunteerism, and feelings of ownership towards the neighbourhood (Gehl, 2018). These two contextual factors, if strong for all social groups, can encourage a more diverse, representative, and therefore inclusive participation, where this does not only entail attendance by all actors, but also the opportunity for equal involvement and equal influence on the outcome. At the same time, participation that is inclusive should promote similar

amounts of civic trust and social capital in all stakeholders. It is only then that the process can be deemed inclusive overall (Sokolaj, 2021).

The process analysis

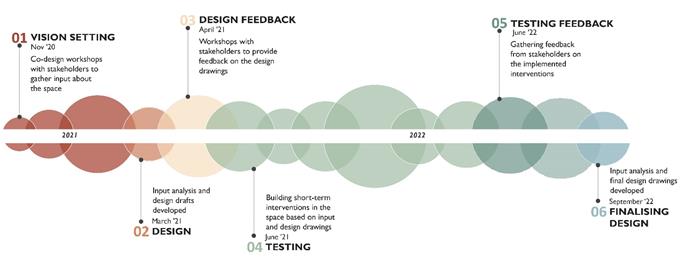

The co-design of Klostergata56 commenced in November 2020 and was organized in six phases (Figure 3). In the first stage of the process, the stakeholders were invited to voice impressions and desired changes for the site, in order to come up with a common vision for the new design. This input was then analysed by the team of facilitators and interpreted into a common design concept and three alternative preliminary solutions. These drawings were as a following step taken back to the participants to receive feedback. Presently, the main features of the design proposal are being tested through temporary tactical interventions. Depending on the testing feedback, the suggested changes will be incorporated into SIT’s final construction drawings for the student accommodation and adjacent space.

Figure 3. The six phases of the co-design process

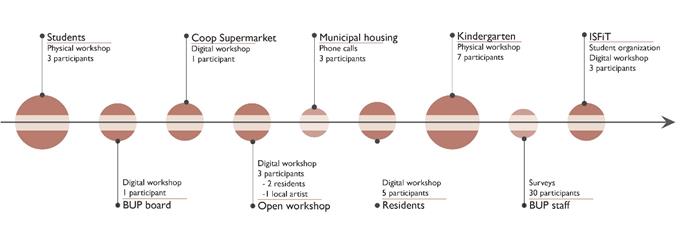

Since the testing phase is still ongoing, the framework was mainly applied to the Vision Setting and Design Feedback phases. The invited participants formed roughly homogenous focus groups with the intention of gathering group-identity perspectives. These groups included students from the area, managers of the supermarket, employers and patients of the BUP rehabilitation clinic, a neighboring Deaf Community Center, general residents, the neighbourhood kindergarten, as well as Municipal housing residents - a mix of locals and refugees who struggle with health issues, addiction, psychological problems, or low income. The process involved two additional external stakeholders - a student organization (ISFiT) and a local artist - who were not directly impacted by the project but expressed interest in participating.

The initial plan to engage all

stakeholders through in-person workshops was quickly abandoned due to a change

in COVID-19 restrictions, so participation was mostly carried out online.

- Participation

Level of engagement. There was a significant drop in the number of participants from the Vision Setting phase to the Design Feedback one (figure 4). This was partially caused by a decrease in number of representatives for the students and the student organization, but mostly because some of the stakeholder groups - the Municipal housing, the BUP staff and the kindergarten - only joined the first phase but did not come back for the other. The interviewed experts pointed out that there is no standard number of a successful rate of attendance - it is more important to have all stakeholder groups represented. However, the residents who joined separate workshops, although of similar profile, had different perspectives about the site. Therefore, the legitimacy of treating the views of a few as representative of others of their kind is arguable.

It is most critical to note, however, that there were several groups completely left out of the entire process. Attempts to engage the BUP clinic patients and the Deaf Center were met with gatekeeping from their administration. On the other hand, considering the residents as a bounded stakeholder unit disguised the fact that certain age groups - older persons and children - were also not being directly consulted. It is most likely that both these groups were excluded because of digital literacy, since the outreach methods and the workshop venues were mainly digital.

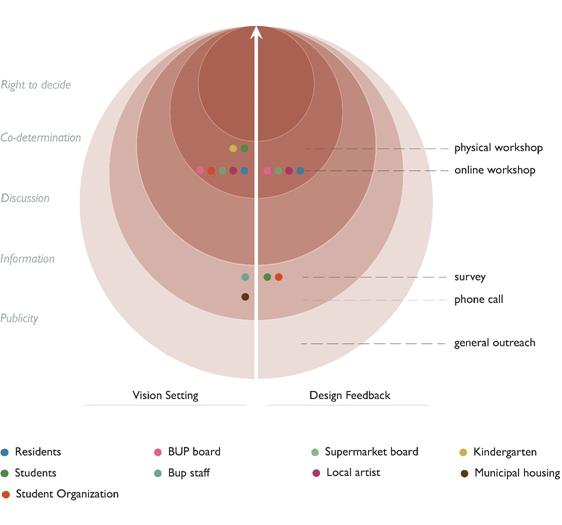

Figure 4. Level of engagement - Vision Setting (above) and Design Feedback (below)

Level of influence. In an attempt to involve groups that were being left out, the facilitators opted for alternative methods when workshops did not appear to be a suitable setting. However, different tools enable different levels of impact on the outcome, depending on their interactivity and communication efficiency. To understand this, the methods used for each interest group were mapped on a scale (Figure 5) for both the Vision Setting and the Design Feedback stages. The engagement objectives - publicity, information, discussion, co-determination and lastly the right to decide - are the adaption of Arnstein’s ladder of participation to the Norwegian context by Fiskaa (2005). Wide gaps between the different groups are an indication of a less inclusive process (Sokolaj, 2021).

Figure 5. Level of influence - Vision Setting (left) & Design Feedback (right) (Adapted from Sokolaj, 2021).

In both phases certain groups, such as the BUP staff and the Municipal housing, stand at a disadvantage. In addition, stakeholders left out of the entire process, as pointed out in the previous section are, at best, in the lowest step of the ladder – Publicity, in case they found out about the process through one outreach method or another.

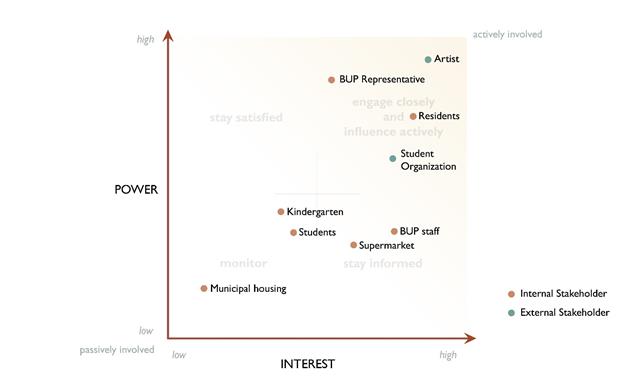

Level of involvement. During the interviews with the participants, they were also asked to pin themselves in a stakeholder matrix (Figure 6), based on their perceived power, and their interest to contribute to the project and collaborate with other stakeholders. Power was referred to as possession of knowledge and skills, informal influence through internal links, access to resources, status of representation or possibility of involvement during implementation (Johnson et al., 2009). The matrix helped reveal stakeholders’ level of involvement from a passive (low interest - low power) to active (high interest - high power) scale, as well as identify the causes of their stance. The more stakeholders are in the same matrix and the smaller the gap between positions is, the more inclusive the process can be considered - and the opposite.

The result showed that the primary interest groups, directly affected by the project as daily users of the site, have a high range of level of involvement, with very few of them - the BUP board and the residents - being in the Key Stakeholders group. The two external stakeholders - the student organization and the local artist - are also in this category. If external stakeholders are more actively involved than many of the primary ones, the level of inclusion of the process becomes a quite evident issue.

Figure 6. Level of involvement map (Adapted from Sokolaj, 2021).

- Social Capital

The interviews with the local planning experts and the process participants revealed that, while there is harmonious coexistence among the diverse groups, the social ties in the neighbourhood are not very strong.

Long residency in an area contributes to social assets like goodwill, bonding and trust with others (Price et al., n.d.), but there is no such glue for many of the groups - the students, the BUP patients, and even the Municipal housing - who only stay there temporarily. Moreover, since the majority live in apartment blocks, they tend to use their own shared facilities rather than neighbourhood’s open spaces. This affects their feelings of ownership over public spaces, but also the frequency and chances of interaction with other groups, which results in low bridging capital.

On the other hand, the most involved resident group have lived in detached housing for a long time and belong to the most organized part of the neighbourhood. When part of placemaking processes, people come together, interact and cooperate, which creates stronger networks and a sense of community among them (Malone, 2019). It can therefore be argued that the current gaps in social capital will only be deepened by the process. This might make excluded or under-represented groups even less likely to be involved in later processes.

- Civic Trust

The interviewed participants expressed trust in the participatory approach, but also StudyTrondheim as facilitating institution. This was demonstrated through recognition of their own input in the new designs, as well as willingness to be part of future similar processes.

Interviews were however only held with the groups that attended both phases of the project. What can be said about the trust of the Deaf community, BUP patients, or older persons, who were left out of the process? How would these groups react, once they learn about the project and realize they were not part of it? Trust is easy to lose, but very difficult to gain (Lehtonen and De Carlo, 2019). Therefore, this project may build trust in the currently included groups and encourage them to participate again, but could also cause mistrust in the excluded ones, thereby making them more prone to later self-exclusion.

Setbacks and recommendations

The three indicators of the framework showed that the process of Klostergata56 had significant limitations in being inclusive. Children, older persons, rehabilitation patients, the Deaf Center community, the migrants and the income poor - marginalized groups already at risk of being left behind - were exactly the least included ones. On the other hand, the actively involved and constantly engaged were a small group of high income, highly educated, cultural creatives.

There were some cases where participants themselves chose to self-exclude, due to lack of interest or practical difficulties related to time. However, as previously mentioned, many of the setbacks to the process being inclusive were caused by the facilitators. Usage of different methods of participation for different groups, while done in an attempt to adapt to their profile or requests, resulted in different opportunities to influence the design. Secondly, treating the categories of stakeholders as bounded units made invisible the exclusion of certain subgroups, for whom the digital venues and outreach methods were inaccessible. Nonetheless, in some cases, even if the setting and method were specifically designed to meet a target group’s needs - such as integrating a sign language interpreter to engage the Deaf Center community, or sending anonymous

surveys for the rehab patients to protect their privacy - their representatives became gatekeepers in facilitating communication.

Challenges were lastly posed by deep-rooted aspects of society, for instance, the social ties and feelings of belonging, determined by ethnicity, length of residency in the area, or socio-economic state.

One’s ability to be part of a decision-making process depends on one’s capital of skills, time and other resources. Faced with the many difficulties of engaging participants, it is easy for facilitators to fall in the trap of relying on a minority of active resourceful citizens who create no friction and are highly interested. The high range of setbacks, caused not only by the facilitators, but also other factors out of their control, makes including everyone equally an ideal seemingly impossible. Even if so, it is crucial for explicit efforts to be put to reach towards it as closely as possible. We cannot, after all, talk about people-centred design, if we are not including a large spectre of the population. It is only through inclusive processes that we can create inclusive spaces, which are high quality, accessible, safe public spaces that welcome and accommodate everyone (Gehl, 2018). Participatory placemaking is moreover not just a means to an end product. The value lies not only in the redesigned public space, but more so in the process itself, as it creates strong relationships and feelings of belonging. If the participating groups are the already privileged ones, empowering and giving ownership to the already better off will increase the inequalities with the rest. This is exactly why it is crucial to have processes that help build capacity and nurture voice, enabling especially the marginalized groups to share their views and empower themselves (Cornwall, 2008).

To encourage inclusive participation for all, we need to increase access for everyone by bringing down attitudinal, physical, social and cultural barriers created by society. It is these boundaries, and not diversity, that hinder an equal basis of participation in society’s physical, social and political realm. While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, combining pro-active efforts in multiple directions can contribute to minimizing said obstacles.

Klostergata56 exposed the importance of extensively analysing the context before a process starts, in order to recognize the existing power dynamics, understand the level of social capital and civic trust, and identify the groups at risk of being excluded. This should lead to a detailed, yet flexible plan with specific goals, regarding the number and type of events, alternative methods of engagement, as well as time and efforts to be invested to reach an engagement as inclusive as possible. Having a set of concrete goals would make it possible to continuously measure if the process is on the right track, and make adaptations in real time if someone is being left behind. Because participatory placemaking is iterative and allows for multiple points of entry to the process, this constant evaluation enabled the facilitators of Klostergata56 to put additional efforts in involving the less included groups later in the testing phase.

Efforts

should be specifically put forth for the process to encourage capacity building

and independent engagement. This can be achieved by ensuring that information

is available in accessible formats, the workshop venues are barrier-free, and

that they incorporate suitable support methods, tailored towards older persons,

migrants, or persons with disabilities, such as sign speaking interpreters,

translators, easy read materials and tactile graphics. Additionally,

appropriate use of notification and announcement should be used for direct

outreach to the intended group, to avoid

dependency on representatives who can act as gatekeepers. With the increase in the use of digital tools, it is also crucial to promote digital equity and make accessibility enhancements to websites, apps, maps and platforms of participation, such as Decidim.

Direct and personal contact is an effective way to establish contact dialogue when other means cannot. Once pandemic restrictions were lifted, the project facilitators were able to organize a pop-up Christmas event in the site. This allowed them to be present where people are, and communicate directly even with rehabilitation patients and migrants from the area. The latter was additionally supported by the presence of multilingual facilitators.

By developing parameters of inclusion, performing constant evaluations and routinely implementing improved measures, communities’ democratic competence and ability to participate will increase. Access and inclusiveness in participatory placemaking can truly be catalysts for change. Co-designing spaces that appeal to all can lead to unified communities and cities that empower and celebrate everyone beyond their differences.

References

Carr, S., Stephen, C., Francis, M., Rivlin, L. G., Stone, A. M. (1992) Public space. Cambridge University Press.

Cornwall, A. (2008) “Unpacking ‘Participation’: models, meanings and practices”, Community development journal, 43, pp. 269-283.

European Institute for Public Participation (2009) Public Participation in Europe: An International Perspective. European Institute for Public Participation Bremen.

Falleth, E. I., Hansen, G. S. (2011) «Participation in planning; a study of urban development in Norway”, European Journal of Spatial Development, 19.

Falleth, E. I., Hanssen, G. S., Saglie, I. L. (2010) «Challenges to democracy in market-oriented urban planning in Norway”, European Planning Studies, 18, 737-753.

Fiskaa, H. (2005) “Past and future for public participation in Norwegian physical planning”, European Planning Studies, 13, 157-174.

Gehl Institute (2018) Inclusive Healthy Places. A Guide to Inclusion & Health in Public Space: Learning Globally to Transform Locally. Available at: https://gehlinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Inclusive-Healthy-Places_Gehl-Institute.pdf

Iwińska, K. (2017) Towards Better Participatory Planning: Guide to Place-Making. Thesis. Netherlands: Utrech University.

Johnson, G., Scholes, K. & Whittington, R. (2009) Exploring corporate strategy: text & cases, Pearson education.

Lehtonen, M. & De Carlo, L. (2019) “Diffuse institutional trust and specific institutional mistrust in Nordic participatory planning: Experience from contested urban projects”, Planning Theory & Practice, 20, pp. 203-220.

Madanipour, A. (2010) Whose Public Space?: International Case Studies in Urban Design and Development, Routledge.

Price, A., Austin, S., Paranagamage, P., Khandokar, F. (n.d.) Impact of urban design on social capital: lessons from a case study in Braunstone. Loughborough University.

Silberberg, S., Lorah, K., Disbrow, R. & Muessig, A. (2013) Places in the making: How placemaking builds places and communities, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 72.

Sokolaj, U. (2021) Inclusion and placemaking based participation, The case of Klostergata 56. [Master’s thesis]. Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

The Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation (2019) Network of Public Spaces. An idea handbook. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/c6fc38d76d374e77ae5b1d8dcdbbd92a/kmd_public-spaces_innmat_eng_org.pdf

United Nations (2015) Habitat III Issue Papers, 11 - Public Space.